Goods-to-Picker Methods and Alternatives

Efficient companies strive to reduce transit times for good reason: it’s costly and wasted effort

The long path from person to product

In a distribution or warehousing operation, the most common working concept is “person-to-goods” order picking, which simply means that order pickers move to storage locations, often pushing or pulling carts and reading orders off the paper. These pickers spend significant amounts of time walking between storage, and are then expected to decipher an order picking sheet. These operations spend lots of money and time and resources on those steps. Picking paths and storage locations evolve as inventory profiles change — and not always for the better.

It’s usually wasted time to direct pickers to a variety of scattered picking locations in a warehouse

Minimizing that time typically means maximizing profitability. When order pickers are spending in excess of 60% of their time on the move, inefficiency is created. And in many cases, it’s needless inefficiency. As inventory changes and SKU counts increase, efficiency drops. We have seen many instances of companies in growth mode struggling with workforce instability while their systems are essentially configured to rely on a relatively stable labor force. At peak times (holidays and other seasonal spikes) this can become untenable. It certainly becomes less predictable.

Moving goods to pickers allows more efficiency because automation and software for analytics and warehouse management or warehouse control systems can be more fully utilized. Goods to person systems are always best approached holistically, with process driving equipment selection or automation, not the inverse; it’s a poor idea to allow equipment to dictate the process. These solutions rarely work for every area of a facility, or for every SKU in the distribution center. It’s all about blending the right solutions.

For a general analysis of common picking methods and productivity rates, see this article.

Accuracy and productivity improvements

Goods-to-picker (GTP) operations help improve order picking accuracy because order picking employees are shown exactly the item needed for their current task. Usually, these systems are deployed with a picking technology such as light-directed or voice-directed picking systems that intelligently direct workers and eliminate the pick ticket. The types of equipment that delivers products to pickers, flipping the dynamic, and eliminating walking steps and transit times, ranges from highly automated to simple manual systems. What are these types of equipment, and how do they stack up for various needs?

Industrial carousel systems

Carousels, which include a range of types including horizontal, vertical, and vertical lift modules, are one of the more flexible GTP options. They can be tied into ERP, WMS and warehouse control systems whether the carousel is in a large integrated system or a point of automation within a larger operation.

Carousels tend to be deployed for component or item level picking, and are ideal for operations that depend on speed. Manual picking can’t match carousels for speed (about 600 lines per hour). Carousels are expensive, but less costly than comparable automation. They are best paired with voice or light directed picking systems.

Like all GTP technologies, carousels limit worker movement. They also help improve inventory security and accuracy while reducing labor costs. See Carousel Systems: Questions to Ask.

Automated storage and retrieval

An automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS) is usually enterprise-level automation that ties an entire facility together. It’s almost always tied to ERP systems and WMS software.

These systems come in a wide variety of configurations, from an even wider variety of manufacturers. They tie into conveyor systems and large-scale storage areas. AS/RS can also include a range of automated industrial vehicles such as STV’s (sorting transfer vehicles) and AGV’s (automated guided vehicles). These often tie into unit load systems by delivering loads to and extracting them from buffers.

Mini-load systems are designed precisely for goods-to-picker operations. Smaller loads like boxes, totes, or other hand-loaded items with the need for dynamic access and shorter cycle times are handled in mini-load.

Unit load systems handle any configuration of materials that can be moved by material handling equipment as a single unit. That usually means a pallet load, but can also apply to containers and bulky, heavy loads of other sizes.

Carton and gravity flow systems

Flow systems aren’t automated but can be tied into automation. They are ideal for carton or each-picks, and typically tie into a takeaway conveyor. In lean applications, they’re often used in conjunction with an assembly work-cell, to feed parts and components to skilled workers without those workers traveling for parts. Since it can be tightly configured, carton flow is an excellent way to deliver goods to pickers in minimal floor space.

Carton flow systems are frequently paired with light-directed picking to improve both picking speeds and order accuracy. Gravity flow systems have been paired with “goods-to-man” robots such as Kiva systems, which frequently deliver shelves of goods to pickers. This approach blends the advantages of first-in-first-out, pick facing, stationary employees, and carton flow.

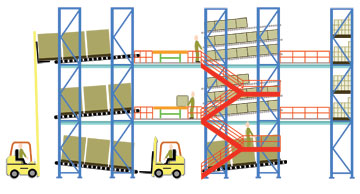

Pallet flow systems

Pallet flow isn’t traditionally considered goods-to-picker, since it delivers full pallets in a first-in, first-out manner. These pallets are typically not picked for individual orders, except when the pallet flow is integrated into a pick module, where pickers break the pallets for carton or case picking to fulfill orders. In this instance, flow racking is loaded from the outside of the pick module by forklifts and flow to workers (usually stationed in a zone near a takeaway line).

Also, workers in a pick module can build pallets for takeaway in the opposite direction, where pallets flow from the elevated area and forklifts can take them away for shipment after they have been built and released from within the module.

These systems have always been ideal where space is limited and pallets are used in part or whole for order fulfillment.

Robotic picking systems

In the last decade or so, the industry has been changed by the proliferation of goods-to-picker robots such as Kiva Systems and others. These systems tend to deliver storage units (shelving) along complex paths, to stationary pickers. Conventional “arm” robots still persist in some picking operations, but are not classic goods to picker technology, since they usually operate without human intervention.

It’s still all about the people

Most of these options are still dependent on people to execute. Finding ways to maximize your labor force is still the goal of most picking and material handling systems due to this. In an era of economic improvement, retaining skilled workers is critical. What these systems allow companies to do is reduce the dependence on labor and focus on hiring, training and retaining the best, most consistent workforce because fewer people are required, and those people aren’t thrown into draining, physically demanding work that reduces their speed and accuracy.

People can always be assisted by direction from WMS or WCS systems. Technologies such as voice-directed or light-directed picking tend to boost accuracy and productivity.

Also, as you probably have experienced, the training curve can be significant, even for every day picking tasks. The opportunity cost of a bad hire can reverberate for months, and goods-to-picker systems help make your operation more attractive to the best workers while reducing the workers you need to hire in order to operate.

Scott Stone is Cisco-Eagle's Vice President of Marketing with 35 years of experience in material handling, warehousing and industrial operations. His work is published in multiple industry journals an websites on a variety of warehousing topics. He writes about automation, warehousing, safety, manufacturing and other areas of concern for industrial operations and those who operate them.